The primary purpose of a documentary, as the word itself suggests, is to document something. When the subject is a specific place at a precise, pivotal point in time, few films accomplish this as comprehensively and effectively as Novo, novo vrijeme (Croatia 2000 – Who Wants to Be the President), the 2001 Croatian film directed by Rajko Grlić and Igor Mirković. The film serves as a masterclass in pure, unadorned political vérité, embedding its audience directly into the chaotic, high-stakes atmosphere of Croatia’s first true democratic transition of power. It is a work of immense historical value, capturing not just events but the very texture of a nation’s political psyche at a moment of profound uncertainty. However, this remarkable achievement exists in a complex tension with the subsequent trajectory of Croatian politics, lending the film a deeply ironic, almost tragic, postscript that its makers could not have foreseen.

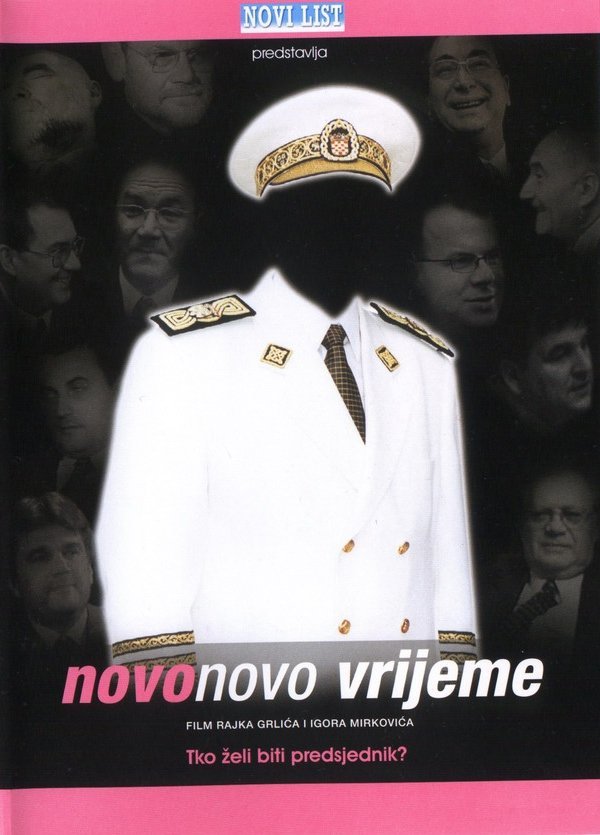

The title itself, Novo, novo vrijeme (‘new new time’), is richly symbolic, borrowed from an eponymous song by the Slovenian rock band Buldožer. The song featured on the soundtrack for the 1979 Yugoslav film That’s the Way the Cookie Crumbles, directed by Croatian filmmakers Bruno Gamulin and Nenad Puhlovski. The choice is pointedly nostalgic, evoking a pre-war, Yugoslav cultural space while simultaneously repurposing the phrase to herald a hoped-for future. The international distribution title, Croatia 2000 – Who Wants to Be the President, while more prosaic, accurately signposts the film’s core drama: a raw, competitive scramble for power in a political vacuum.

The film documents what was perhaps not the most consequential, but certainly the most dramatic and unpredictable election contest in modern Croatian history. It was the first election to result in a peaceful, democratic change of government since independence—an independence achieved under the towering, now-ailing figure of Dr. Franjo Tuđman. By the late 1990s, Tuđman’s reputation as a wartime leader and founding father was severely tarnished. A decade of his rule had left Croatia economically strained, scarred by the brutal toll of post-communist privatisation, and mired in corruption scandals linked to his Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ). More damningly, Tuđman had cemented an authoritarian style, maintaining an iron grip on the media, persecuting political opponents, and dismissing critics as traitors or ‘foreign agents’. The film briefly recaps this context before plunging the viewer into November 1999, with Tuđman terminally ill in hospital. His imminent absence creates a seismic shift; the HDZ must face an election without its founding patriarch.

Tuđman’s death on 10 December 1999 opens the field for a presidential election and unleashes waves of political realignment. The film expertly tracks the fragmentation and manoeuvring within the opposition bloc, a coalition of six ideologically disparate parties. The alliance between the centre-left Social Democratic Party (SDP), led by former Communist Ivica Račan, and the nominally liberal Croatian Social Liberal Party (HSLS), led by former nationalist dissident Dražen Budiša, emerges as one pole. Here, Račan eyes the Prime Minister’s office while Budiša, confident and ambitious, pursues the presidency—a role endowed with significant executive power under the 1990 Constitution. The film captures the other four opposition parties—the conservative Croatian Peasant Party (HSS), the Liberal Party (LS), the centrist Croatian People’s Party (HNS), and the Istrian Democratic Assembly (IDS)—in tense deliberation. They must choose between their own leader, Zlatko Tomčić of HSS, and Stipe Mesić of HNS, a fascinating figure who had been Tuđman’s right-hand man before a dramatic falling-out and who served as the last nominal president of a dissolving Yugoslavia.

The narrative tension is superbly sustained. Initially, the soft-spoken HDZ foreign minister, Mate Granić, appears as the ruling party’s best hope—a moderate seemingly untainted by the worst party scandals. Early polls even suggest he could prevail. Yet, the film reveals the deep internal factionalism within the HDZ that almost derails his candidacy. The tectonic plates truly shift with the parliamentary election of 3 January 2000, where voters deliver a decisive verdict against the HDZ, handing victory to the opposition parties. This result fundamentally alters the presidential race, making an opposition victory almost inevitable. Budiša’s confidence remains unshaken, but the ground is moving beneath him. Tomčić, reading the political winds, abandons his own presidential bid and throws his support behind Mesić. On 24 January, a weakened Granīć is eliminated in the first round, setting up a runoff between Budiša and the surging Mesić. The film’s climax charts Mesić’s dramatic rise: as Račan is sworn in as Prime Minister on 1 February and Tomčić becomes Speaker of Parliament, Mesić secures a decisive victory over Budiša on 7 February, being inaugurated as president on 18 February. The democratic transition is, cinematically, complete.

The film’s power is inseparable from the backgrounds and partnership of its directors. Rajko Grlić, a celebrated filmmaker and a key figure of the ‘Prague School’ within late Yugoslav cinema, brought a sharp intellectual and artistic vision. Like many urban intellectuals of his generation, he viewed Tuđman’s authoritarianism as anathema to a modern European democracy. Igor Mirković complemented this with crucial practical experience. As a Croatian state television reporter throughout the 1990s, he possessed not only the journalistic instincts for the story but, critically, the extensive network of personal contacts across the political spectrum necessary to gain the unprecedented access that defines the film.

Inspired by American documentaries chronicling U.S. presidential campaigns, Grlić and Mirković adopted a deceptively simple yet logistically monumental approach. They embedded camera crews with politicians from both the HDZ and the various opposition factions, as well as key media figures, aiming for a relentless ‘fly on the wall’ perspective. The result was a staggering three hundred hours of footage, meticulously condensed into feature film format. The material is remarkably intimate: candid interviews, feverish strategy sessions in back rooms, public rallies, whispered corridor conversations, and politicians in unguarded moments on the campaign trail. This method grants the film an authenticity that scripted drama could never achieve.

This very authenticity, however, renders the film a challenging watch for those unfamiliar with the intricate personalities and factions of turn-of-the-millennium Croatia. The parade of names, parties, and acronyms can be dizzying. Yet, this complexity is also the source of the film’s fascinating depth. It immerses the viewer in a period of utter uncertainty, where outcomes were genuinely unknown. The producers’ access to internal debates yields moments of profound, unintentional irony that border on the comical. One of the most memorable scenes features Ivan Jakovčić, leader of the Istrian IDS, confidently asserting that Stipe Mesić ‘could not win more than five percent of the vote.’ The humour derives from the audience’s hindsight, watching as Jakovčić’s own party officials later report that their Istrian constituents overwhelmingly prefer Mesić over Tomčić, forcing a swift and sheepish recalculation. It is a perfect vignette of how political certainty can evaporate overnight.

For all its strengths, the film is not without stylistic and narrative missteps. The directors occasionally lapse into somewhat contrived cutaways that disrupt the otherwise compelling central narrative. The repeated footage of NGO activists encouraging citizens to vote, while well-intentioned, begins to feel didactic. Similarly, scenes of street debates among elderly, typically conservative citizens of Zagreb, though offering a slice of public sentiment, often lack the revelatory punch of the behind-the-scenes political footage. The inclusion of rock musician Goran Bare, an SDP supporter, as a kind of informal commentator feels particularly incongruous and adds little substantive analysis, coming across as a gratuitous nod to ‘cool’ credibility rather than an integral part of the story.

The film’s greatest poignancy—and its central irony—lies in the chasm between its hopeful title and the subsequent course of Croatian history. Novo, novo vrijeme promises a dawn. The reality that unfolded was a return to a familiar twilight. The ‘first true multi-party government’ portrayed in the film’s euphoric final act began to fracture almost immediately, largely due to personal animosities, with a embittered Dražen Budiša, deprived of the presidency, turning sharply against his coalition partner Ivica Račan. More startlingly, the HDZ, which the documentary portrays as a mortally wounded beast tearing itself apart in internal disputes, did not vanish into the dustbin of history. Under the leadership of Ivo Sanader, it regrouped, rebranded, and triumphantly returned to power just three years later in 2003. Despite the corruption scandals that would eventually engulf Sanader and others, the HDZ—with only a brief hiatus between 2011 and 2015—has maintained its dominance in Croatian politics to the present day. The film documents a ‘new time,’ but real history, shaped by voters ultimately disappointed with the infighting and unmet expectations of the 2000 transition, opted largely for ‘the same old, same old.’

This dissonance does not diminish the film’s value; it enhances it. Viewed today, Novo, novo vrijeme is not merely a record of an election. It is a fossil preserved in the amber of a specific, fleeting optimism. Its 2001 cinema popularity can be attributed to that widespread, euphoric feeling that Croatia was finally advancing toward being a ‘normal’ democracy and a prosperous European country—a sentiment the film both captures and amplifies. For contemporary audiences, especially cynical ones, the film offers a powerful, even melancholic, experience. It allows for a comparison between that promising, volatile past and a often depressing present. Furthermore, the intimate portrayal of political manoeuvring, cluelessness, dysfunction, and at times comical incompetence among the Croatian elite feels less like a distant historical artefact and more like a timeless, universal study of political mechanics. In an era where similar traits are readily observable in the offices of Brussels, Washington, and other world capitals, the film’s examination of the gap between democratic idealism and political reality remains painfully, and brilliantly, relevant.

RATING: 7/10 (+++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Leodex: https://leodex.io/?ref=drax

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9